Do want to kick back and relax with a great book during the holidays? Join us as we talk about three captivating books speech therapists can relate to.

—- Links —-

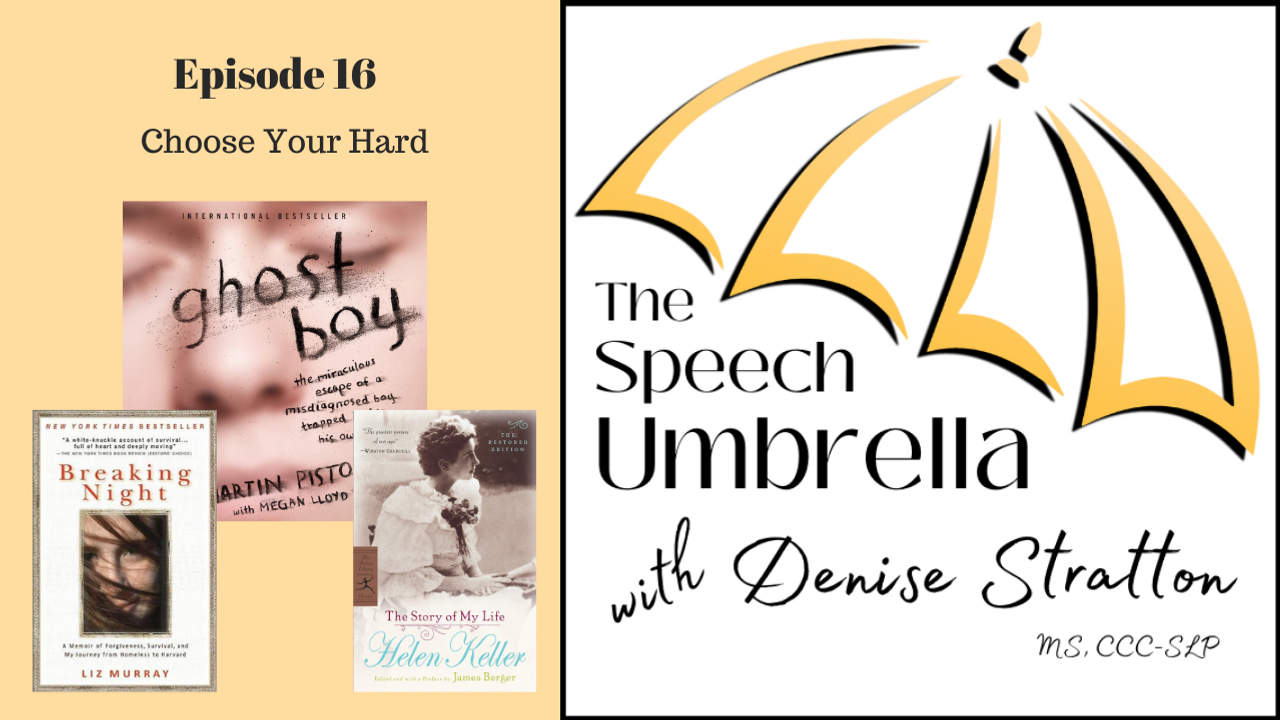

Ghost Boy by Martin Pistorius

Breaking Night: A Memoir of Forgiveness, Survival, and My Journey from Homeless to Harvard by Liz Murray

The Story of my Life: The Restored Edition by Helen Keller

Music: Simple Gifts performed by Ted Yoder, used with permission

Dan: Welcome to The Mindful SLP, the podcast for SLPs looking for simple tools and optimal outcomes. Your host is Denise, experienced speech therapist specializing in all things pediatric, and Dan, business manager for her private clinic.

Welcome back to The Mindful SLP. Hey it’s time for a little bit of R&R. This week, we’re going to be talking about three books Denise has read that she found to be very fascinating from a speech therapy perspective. The three books are Ghost Boy by Martin Pistorious, Breaking Night by Liz Murray, and The Story of My Life, the Restored Version, by Helen Keller.

Now, Denise, I know that you really enjoy autobiographies. I see you reading them most of the time. What is it that gravitates you to biography stories about people?

Denise: I love to read about people who overcome whatever life throws at them. I’m just fascinated by people who develop strength of character and show amazing resourcefulness in difficult situations.

Besides the strength of character displayed by the people in these books, Martin and Liz and Helen and Ann, there are a few points that really interest me as being relevant to our profession, and that’s another reason I chose to highlight these three particular books today.

Dan: Well, let’s start off by talking about Ghost Boy by Martin Pistorious, what drew you to this book?

Denise: Well, the headline about Martin just grabbed me right away. It reads, they all thought he was gone, but he was alive and trapped inside his own body for 10 years. Well, I wanted to know how he came back, how that all happened.

Dan: Well, give us some background, how did he get trapped?

Denise: Well, Martin became mysteriously ill when he was 12. And over the next 18 months, he lost all of his motor function, his ability to speak. He ended up in a wheelchair. He was unresponsive. And actually he has no memory of the first four years after that happens. Then when he was about 16, he began regaining consciousness and he was aware of what people were saying around him, he understood it. By the time he was 19, he was fully aware but he had no way to communicate to people that he was aware. He could communicate with his eyes, but nobody knew that. Wow. And so that’s when my speech therapist side kicked in and I was like, somebody get him an AAC device, someone look in his eyes and notice that he is trying to tell you something.

Dan: I guess that’s what happened since he wrote a book, obviously, about his experiences, but how did that happen? Who noticed that he was aware?

Denise: There was a character named Verna who was a massage therapist and Martin writes about how he so looked forward to her visits because she deeply cared when she was with him. She had conversations with him and somehow she was able to establish a connection with him in spite of his condition. And she’d gone to an in-service on AAC devices and thought that Martin would be a great candidate. So that brings me to the first point I want to emphasize that we SLPs can particularly relate to, it’s to assume competence, and Susan Berkowitz, who is a specialist in AAC, a speech therapist who is a specialist in AAC, says always assume your client has the competence to communicate if you provide the right tools. And I think to myself, what a Verna had not thought about Martin.

Dan: That would have been a tragedy. He just, he would’ve just remained trapped forever. Oh, what a life!

Denise: I mean, you can’t even bear thinking about it, but instead, now he’s married and he runs his own business. Um, on his website, it says he does wheelchair racing.

Dan: Wow, talk about overcoming. Well, tell us a little bit about Martin’s AAC device. I’ve heard you talk about them, and I have a very little knowledge about them. I mainly know about Stephen Hawking’s.

Denise: So initially Martin was going to get a device that was programmed with 200 words after the assessment. That’s what the team kind of decided. Now that may seem like a lot of words for someone who hasn’t said a word in years, but Martin’s heart sank when he realized that he was going to be limited to 200 words with all the words he had inside of him, everything he wanted to say it was depressing for him, but he couldn’t tell anyone.

Dan: Well, as a 12 year old, he’s going to have way more than 200 words in his vocabulary. And I bet, I’m assuming he didn’t lose any vocabulary while he was, uh, in this state. That would have been a really difficult thing.

Denise: Fortunately for him, that plan fell through. He ended up with a regular computer with AAC software, and then of course the sky was the limit, but here’s another SLP moment.

It’s so important to give our clients as much vocabulary as they can handle. So Martin describes this moment when his mother was inputting words for him. So she did have to input words for him so that they were in the memory of the computer. But Martin hadn’t regained his ability to spell. So he can’t speak, he can’t spell. Sometimes it’s a bit of a guessing game, right? He’s from South Africa and he was longing to describe the color of the sky in summer. And he wanted to use the word turquoise. His mother was trying so hard. I mean, she knew it was a color. She just couldn’t get turquoise. Um, but he uses the word longing that he was longing to use that word.

And that just really struck a chord with me. It’s very, very important that we give our kids vocabulary.

Dan: Yeah, well, what’s the third thing you learned from this book?

Denise: So my third and final takeaway from Ghost Boy is about the power of decision-making. Now I mentioned earlier, the Martin could only communicate with his eyes, but eventually he regained some hand control.

And so he was using his hands to operate his AAC device and the technology at that time required him to choose a word as it scrolled past on his screen. So one morning his plan was to type out what he wanted for breakfast. But he missed a word as it scrolled by and he had to wait for all these other words to scroll by, basically start over again before he could capture that word again, because of his poor hand control.

It took him a really long time, but it was really super empowering for him when he was able to type out what he wanted for breakfast. So the power of decision-making, because before that, you couldn’t tell someone if he hated the food, if he wanted salt, if it was too hot, if it was too cold, nothing.

Dan: That would be a challenge.

Denise: But now contrast that empowering decision making moment with his first visit to England, to see his girlfriend. And she said, Hey Martin, I think you need new shoes. So she took him to a shoe store. Now for years he had been wearing the same brand, same pair of brown shoes, very serviceable. And when they wore out, his parents just got a new ones. And now he’s in the shoe store, which you’ve been in a shoe store, right. Looking at all of those choices so overwhelmed him that he started crying. He was so embarrassed. I mean, he’s in public, he’s there with his girlfriend. It was just too much for him. His girlfriend later, his wife, her reaction is wonderful.

She’s like, you know, we’ll get through this together. This was just too much today. But I thought it was very interesting because I have seen my own clients when they have the power to choose, how excited they get. I’ve also seen them overwhelmed by choice. So we need to help them grow into choosing.

Dan: Wow, that’s that’s really good. Now I want to read it. Okay, that’s Ghost Boy by Martin Pistorious. Let’s move on to Breaking Night by Liz Murray. Now you’ve, you’ve brought her story up several times while you were reading it. In fact, I used to get a debrief just about every day on it. Tell us a little bit about Liz Murray.

Denise: Her parents were both drug addicts and their addictions were so consuming, it just took over their lives. Um, she didn’t like to go to school. Now can you guess why? She was hungry, she was tired, she was dirty, she smelled, which the other kids didn’t hesitate to point out and it was easier to stay at home and her mother let her.

Dan: Yeah. So if no one’s pushing her, no, one’s expecting anything from her. What’s she gonna do?

Denise: And of course she gets farther behind. So then it’s even harder to go. And as she got older, she got really, really good at circumventing the truancy system. So she knew how to intercept letters and how to intercept phone calls.

By the time she was in high school, she was basically a high school dropout. And one day she did go to a high school history class with her friend, just on a whim and she aced the test on the Civil War. Because her father was a great reader. That’s one advantage she had, she’d read a book on the Civil War and she knew the answers. And that high school teacher took her out in the hall and pleaded with Liz to come to school. And what she said was, I understand why you don’t come to school and it’s not your fault. You are a victim of these things. I understand. Her teacher had tears in her eyes and she really did care, but Liz said all I heard was I didn’t have to do my schoolwork for reasons that were not my fault. I didn’t want to do my work anyway. So that was great.

Sometimes we have to hold people accountable.

As much as you care, accountability is really important. Now, contrast that with the attitude of the teachers at her alternative high school, when she did get into an alternative high school. They also care, but they had really high expectations. They expected her to not be a victim. It was a different kind of caring, but it was the caring she needed. That’s one of the points I want to bring out in Liz’s story, as teachers and clinicians our clients need us to both care about them and hold them accountable.

Dan: It’s important to hold our clients accountable, but you also talked about how Liz started to hold herself accountable. Had she already made the shift to accountability when she started at that alternative high school?

Denise: This is one of my favorite parts of her story. She left home when she was in her teens, so now she’s a high school dropout and homeless. She spent a lot of nights on friend’s couches and on floors, sometimes in stairways. But it seemed like she was always dropping in on her friends and asking for a meal or asking for a shower, and sometimes her friends snuck her past their parents. Sometimes it was with their parent’s permission, but Liz noticed that having to depend on her friends for these favors changed the relationship.

It wasn’t really a true friendship anymore. And so one day she had this epiphany friends don’t pay your rent. That’s when she decided to graduate from high school, come hell or high water. She developed an amazing internal drive and she did not allow herself to slack off. And she started looking for an alternative high school and several of them turned her down, but she persisted in applying, which was something she hadn’t done before.

She hadn’t persisted before. In fact, on the day that she got into this wonderful high school, she ended up at, she had a really significant debate with herself on whether she should go buy pizza with her money or buy the bus ticket to go to the alternative high school. Well, the pizza lost out and thank goodness.

Dan: So she had really just started to hold herself accountable. So what’s another takeaway from this story.

Denise: You can do a lot for your clients, but the internal drive has to come from within them.

Dan: Well, I understand Liz had so much drive that she actually got into Harvard and won a very prestigious scholarship. Tell us more about that.

Denise: Okay. This is one of the funniest stories in the book, the story about her scholarship interview. She was a finalist for the New York times scholarship, but she had absolutely no idea how important the New York times was. No one in her circle read it. All the scholarship finalists were scheduled to do an interview. And on that day of interview, she had packed a lot of errands into her schedule that day, probably because she didn’t want to miss any school, that commitment she’d made to herself. She was like, okay, I can get everything done on this day. Then I’ll go to my interview. And when she got to the lobby, she was just kind of tired and glad for a chance to sit down.

She didn’t even notice how tense it was in the lobby. These parents and these other students are so hyped up for this really, really prestigious scholarship. And she was just like, I got a chance to sit down. And then there were donuts and muffins in the lobby and orange juice. And the secretary said, oh no, one’s touched these help yourself. And Liz was like, sure, this is free food. And she opened her backpack, and when the secretary wasn’t looking she swept a whole bunch of donuts and muffins into her backpack. And that’s so funny. And she goes into the interview, she’s got sugar on her hands from the donuts, and she grabs a tissue and says, excuse me, I gotta wipe my hands. She was just clueless about the importance of the scholarship, I guess.

Dan: She’s still managed to just relax. What does she tell them?

Denise: Well, she told them her story first about being homeless. And then someone asked her, well, why should we give you this scholarship? And she said, well, I just really need it.

Dan: That’s amazing. So tell me about the final takeaway from Breaking Night.

Denise: It’s what Liz said. I have learned that no one, no one truly knows what is possible until they go and do it.

Dan: Wow. That is important. Say that again.

Denise: I have learned that no one, no one truly knows what is possible until they go and do it.

Dan: Speaking of impossible, Helen Keller story seems to be one of those. It’s on the verge of impossible. Most people are familiar with her story, but what drew you to it? And what can an SLP take away from The Story of My Life?

Denise: Yeah, so we wonder, okay, what’s new, what’s new for SLPs. Um, first of all, The Story of My Life, the Restored Version, is not a typical autobiography.

Dan: What do you mean by that?

Denise: The Restored Version has material besides Helen’s memories. Um, oh, by the way, she was in her early twenties when she wrote it. So it’s only part of her life, but it has letters that Anne Sullivan wrote about her teaching methods and comments by other people who knew Helen or studied her. So the Restored Version is the one I read, that’s the one I recommend, because of all this additional material.

Dan: We’ll have to be a downer, but that sounds like a lot of stuff to pack into an autobiography.

Denise: I happily admit that I skipped around the book. Didn’t want to read every single thing. What I absolutely love are Anne Sullivan’s letters about teaching Helen, Helen’s observations about when she discovered language. Those are my favorite parts of the book, Anne was way ahead of our time at understanding how to teach language and what she wrote is still relevant today. I’ll pull it up and I’ll read it like, yeah, I think to remember that, I need to remember that when I’m working with my clients, I could spend way too much time quoting Anne, I’m just going to try and stop it at three things about teaching language.

So I want to talk about self-regulation, um, learning language, and finally, an interesting perspective on Helen’s character.

Dan: Alright, let’s start with self-regulation.

Denise: Well Anne realized right away that unless Helen could regulate her emotions, she would be unteachable. Um, Helen’s family always gave in for the sake of peace and Ann wrote “Nobody has ever seriously disputed her will, every thwarted desire was a signal for a passionate outburst.”

Dan: You’ve never experienced a client like that.

Denise: I have, um, I mean, Helen had that great strength, which served her well later.

Dan: A real obstacle to overcome at the beginning.

Denise: When she was not in control of her emotions. Yeah. Everything just had to go her way or she fell apart.

Dan: Well how did Anne start doing that?

Denise: Well, eventually she convinced Mr. & Mrs. Keller to let them move into a garden house, just the two of them so that Helen could learn to trust her and be reasonably obedient. I love how Anne Sullivan said reasonably obedient, she’s a child, right? Um, they had some titanic struggles, but Helen did learn to self-regulate. It took about two weeks, just the two of them, 24-7.

Dan: Well, what did you learn here?

Denise: Well, Anne said at best, I have done my best to make them see the terrible injustice to Helen of allowing her to have her way in everything. So we do injustice to our children, to our clients. If we don’t help them learn self-discipline and self-regulation, it’s like stopping their growth path. And also I have seen this in clients that they achieve a kind of peace within themselves when they can self-regulate. And Anne wrote about that too, that people commented that Helen could be still, that she was no longer constantly restless, constantly moving. She had some kind of internal peace.

So nowadays as SLPs we’re more likely to see kids with autism, with the struggle with self-regulation. But it isn’t necessarily just kids with autism, but it’s the first thing I think about with any new client, because it’s the doorway to learning.

Dan: Well, how did Anne teach language? This is part of the story that seems so impossible because Helen developed language at a very high and sophisticated level, but yet she had very little to reference from.

Denise: Yes. I mean, she was in 19 months when she got ill. Um, well, one of Anne’s techniques was she exposed Helen to lots of language by spelling into her hand all day long. Anne wrote, “I will pour words into her.” So exposure, exposure, exposure. And now we know how vitally important language exposure is, but this was something Anne figured out on our own, the kids hear millions of words, before they even begin to speak. And she knew that Helen needed that constant input. So that was the first thing, I actually broke down language into three parts. So the exposure, the pouring words into Helen. Okay. And then she figured out how to communicate the nature of language to Helen, that it is both specific and general.

Dan: Specific and general, what, what do you mean by that?

Denise: Okay. We’re taking a dive sort of into linguistics here, but when I say water, I could be talking about the water in my glass, and that was very specific. Or I could be talking about the water in ocean, lakes and rivers, which is general. And this is a concept that was really confusing Helen. On the day, she had that famous moment with the water at the pump where she remembers that word Wawa for water. All day, she’d been confused about the words mug and milk and water cause her milk and her water were always in her mug. So were they separate things? Were they the same things? I mean, she just didn’t understand that concept. And so Anne thought, well, if I take her outside and if I pump water over her hand, maybe that’ll help her clear this up.

And of course, we all know how that turned out. That’s not new, but what was new to me is Helen referred to that date ever after as the day I learned everything had a name, which is just so interesting because I find that children I work with who are learning to use AAC devices, they have the same struggle that Helen did to learn that everything has a name.

They might know that pushing this button, activates something.

Dan: But that doesn’t necessarily make that connection yet.

Denise: Yeah I have a client right now who does know that ball means ball, but he also pushes ball for everything he wants to happen. Hm. So he does not know yet that everything has a name, just that he can make certain things happen by activating certain things.

Dan: Well tell me about the third point that you learned.

Denise: Anne figuring out how to communicate the idea of abstract language to Helen.

Dan: So that’s gotta be really hard.

Denise: I know it’s even amazing to me. And of course we do realize that Helen was very, very bright. So it was Anne Sullivan. Helen was stringing beads in a pattern and she kept making mistakes.

Finally, she noticed her error. She concentrated her attention and tried to think it through. This is what Helen wrote, “I concentrated my attention and I tried to think it through.” And while she was concentrating Anne touched her forehead and spelled think, and Helen wrote “in a flash, I knew that the word was the name of the process that was going on in my head.”

So while it’s important to realize that Helen was very bright, I think even gifted, and that helped her with her many remarkable achievements, we still need to assume competence in our clients and take them as far as they can go.

Dan: Wow. That’s that’s important. Well, let’s wrap this up by talking about the perspective on Helen’s character. You mentioned you’ve kind of got passionate about that.

Denise: Yeah, I did. And the name of this podcast, which we haven’t referred to yet, but it’s called Choose Your Hard. Okay, so we’re going to get into that. But, um, remember I said, the book included people who studied Helen’s life. It’s got some commentaries. Um, Helen has obtained almost a mythical aura because she was so good, by everything I’ve read by all accounts, she was happy for giving, kind, and devoted to helping improve the position of others with disabilities. Plus, she had a sense of humor. Well, one scholar suggested that she was so good because all the literature that she read at that time portrayed children as models of virtue, and so that’s what Helen became because that’s what she read.

And I just think that idea really does Helen a disservice, to say that she obtained a kind of superficial goodness. Um, it really takes from her the power to choose to be good. And they say she was naive about the world too. That was part of this explanation of why she took on this persona of goodness, but I’m sure she was naive about some parts of the world and I’m sure I am naive. I’m sure we were all naive about certain parts of our world. We’re very naive about what it is to be deaf and blind, like Helen was.

Dan: You and I were talking earlier about choosing your hard in connection with Helen. Tell us more about that.

Denise: Maybe you’ve seen the internet meme, choose your hard. And they go like this. Losing weight is hard. Being overweight is hard. Choose your hard. Or changing is hard, not changing is hard, choose your hard. Well, I have really believed that Helen woke up every day and chose her hard, and that choosing was what formed her strength of character.

Dan: And you could say that about Martin and Liz as well. They chose their hard.

Denise: They all did, I guess that’s why I love these books, I love books about people who choose their hard.

Dan: And just like you, you’re choosing your hard too. I remember the days when you were terrified of sitting down in front of a microphone.

Denise: Actually this podcast was kinda hard. There’s been a couple of rewrites.

Dan: Well, thank you for joining us. In this coming year of 2021, we challenge you to choose your hard. There’s going to be something that’s going to really crop up, that’s going to really give us a run for our money. Choose your hard. How are you going to handle it? Maybe you ought to grab one of these books and kind of see how other people did it so that you can learn something that’ll help you when you choose your hard.

Come back next time and we’ll be talking about R therapy. So we look forward to talking with you in the new year. Thanks for listening. Thank you for listening to The Mindful SLP. We hope you found some simple tools that will have optimal outcomes in your practice. This podcast is sponsored by SLP ProAdvisor.

Visit SLP pro-advisor dot com for more tools, including Impossible R Made Possible, Denise’s highly effective course for treating those troublesome Rs. A link is in the show notes. If you enjoyed this podcast, please give us a five-star rating and tell your fellow SLPs. And please let us know what you think. Join the conversation at SLP pro-advisor dot com.

I am a therapist and entrepreneur, clinic owner, published author, and creator of speech therapy materials.

The Speech Umbrella is run by Denise Stratton, Reach out with any questions.